The Golden Thread: A History of Olive Oil in Albania and Kosovo

The Tree of Life

In the hills near the Albanian village of Brret, in the region of Krujë, stands a living monument. It is an olive tree, but not just any tree. Its trunk is a gnarled, sprawling giant, with a perimeter of up to 30 meters, a testament to the passage of time. Scientists and historians estimate its age to be around 3,000 years. This single tree was a sapling when the Trojan War was still a recent memory and the city of Rome was yet to be founded. It has stood silent witness to the entire sweep of Albanian history, from the ancient Illyrian kings who carved olive branches onto their shields, to the Roman engineers who built sophisticated presses, the Byzantine traders who shipped its oil across the sea, the Ottoman pashas who ruled the land for centuries, the communist tractors that reshaped the landscape, and the modern farmers who now tend its descendants.

This ancient tree is more than a biological wonder; it is a symbol of the story this report will tell. The history of the olive tree and its precious, golden oil is a golden thread woven deeply into the fabric of Albania’s identity. It is a story of resilience, of a culture that has endured through the rise and fall of great empires and the immense turmoil of the 20th century. The olive has been a source of food, light, wealth, and sacred ritual for the people of this land for millennia.

This report will follow that golden thread through time. We will begin our journey in the deep past, when wild olives first grew on the Balkan Peninsula during the last ice age. We will travel through the ancient world to see how the Illyrians became masters of cultivation and how the Greeks and Romans helped turn their oil into a prized commodity. We will explore how the tradition survived through the long medieval period and the Ottoman era, becoming a cornerstone of family life. We will then navigate the turbulent 20th century, a time of both massive expansion and devastating destruction for Albania’s olive groves. Finally, we will arrive in the present day to understand the challenges and triumphs of the modern olive oil industry in Albania and to explore the unique story of the olive in neighboring Kosovo, a land with a different but equally important agricultural heritage. This is not just the history of a fruit; it is the history of a people, told through the leaves, branches, and liquid gold of the olive tree.

Part I: The Ancient Roots

Chapter 1: Echoes in the Earth: The First Olives

Long before the first cities were built or the first words were written, the story of the olive in Albania had already begun. This story does not start with a farmer planting a seed, but with the wild and rugged landscape of the Mediterranean itself. For tens of thousands of years, a wild version of the olive tree, known to scientists as the oleaster or Olea europaea oleaster-sylvestris, grew naturally across the region, including on the lands that would one day become Albania. Archaeological discoveries, like fossilized olive leaves found in layers of lava on the Greek island of Santorini, show that these wild trees have been part of the Mediterranean world for at least 60,000 years. In Albania specifically, evidence of these ancient oleasters dates back as far as 12,000 to 60,000 years, suggesting that the region was not merely a place where the olive was later introduced, but part of its original, natural homeland.

For countless generations, early humans would have gathered the small, bitter fruits of these wild trees. But a monumental change occurred during the Neolithic period, a time of great innovation that began around 6000 BC. This was when people across the Mediterranean first learned the revolutionary art of farming. They began to domesticate the wild olive, carefully selecting and planting the trees that produced larger, oilier, and better-tasting fruit. This slow and patient process marked the birth of the cultivated olive,

Olea europaea sativa. Due to Albania’s close proximity to Greece, where this process was also unfolding, it is believed that the domestication of the olive began in Albanian territories around the same time, some 6,000 years ago. The first evidence of this cultivated olive in Albania appears around 5,000 years ago, primarily in the country’s central and southern regions.

This incredible agricultural breakthrough was not an isolated event. The knowledge of how to cultivate olives spread like wildfire across the ancient world. It was carried in the minds of farmers and in the hulls of ships belonging to great seafaring peoples like the Phoenicians. These expert traders from the coast of modern-day Lebanon traveled throughout the Mediterranean, establishing trade routes and sharing knowledge. They are credited with helping to spread the cultivated olive tree to western parts of the Mediterranean, including the sun-drenched coasts of Illyria, the ancient name for Albania. This ancient history is important because it shows that Albania was an original and foundational part of the olive’s story. The land was already home to the olive’s wild ancestors, making it fertile ground for one of the most important agricultural developments in human history.

Chapter 2: Liquid Gold of the Illyrians

The ancient Illyrians, the ancestors of the modern Albanian people, were the first to truly harness the power of the olive tree and make it a cornerstone of their civilization. They transformed olive cultivation from simple farming into an art and an engine of their economy. Ancient writers from neighboring lands took notice. The Greek geographer Scymnus, writing three centuries before Christ, described Illyria as a “warm prosperous country, filled with good olive orchards and vineyards”. The Illyrians were widely known as masters in the cultivation of both olives and grapes, and the oil and wine they produced were famous.

For the Illyrians, olive oil was far more than just a food source; it was liquid gold. It powered their economy and fueled their trade. Archaeological digs in ancient Illyrian cities like Amantia, Bylis, and the great port of Apollonia have uncovered countless storage containers, large jars, and amphorae specifically designed for holding and transporting olive oil. This shows that oil was being produced on a massive scale, far beyond what was needed for local consumption. It was a valuable commodity, and the Illyrians established vibrant trade networks, selling their oil to Greek colonies and other peoples in exchange for weapons, tools, and other essential goods. One powerful Illyrian tribe, the Moloses, was particularly influential in spreading the culture of the olive, using their trade agreements and control of ports like Apollonia and Aulona (modern Vlora) to push cultivation as far north as Shkodra.

The olive tree was woven just as deeply into the cultural and spiritual life of the Illyrians. It was a sacred tree, a symbol of peace, life, and victory. The people of Epirus, a region of Illyria, had a beautiful tradition of using wreaths made from olive branches. These wreaths were placed on the heads of warriors who had performed great deeds for their homeland and were also used to bless new brides, a symbol of happiness and prosperity for the new family. This powerful connection is also seen in their art; archaeologists have found images of olive trees and fruits carved into the shields of Illyrian warriors and on stone bas-reliefs, a permanent declaration of the tree’s importance to their identity. To the Illyrians, the olive was a gift that had lifted their people up, a force that, in the words of one historian, “emancipated them, saved them from barbarism and increased culture and civilisation”.

One of the most telling signs of the olive’s immense value is where the Illyrians chose to plant their most important groves. Across Albania, a remarkable pattern has been discovered: the oldest and grandest olive groves are almost always found clustered around the ruins of ancient castles and fortresses. Researchers have identified at least 42 ancient castles that are surrounded by 53 villages possessing some 136,000 ancient olive trees. This was no accident. Castles are built to protect a society’s most critical assets. For the Illyrians, the olive groves were a strategic resource, as vital as a modern nation’s oil fields. They provided food for the people, fuel for lamps, and a product that could be traded for military supplies. By planting their groves within the protective shadow of their fortifications, the Illyrians were essentially placing their economy and their way of life inside a vault, safeguarding their liquid gold from raiders and ensuring the survival and prosperity of their cities. The very landscape was organized around the protection of this precious resource.

Chapter 3: The Roman Press

When the powerful Roman legions marched into Illyria and conquered the region, they did not find a backward land. They found a territory already rich in olive groves and a people who were experts in their cultivation. The great Roman general and statesman, Julius Caesar, personally commented on the region’s wealth, describing the city of Aulona as a beautiful, developed place with widespread olive groves that were of great economic importance to the country. The Romans, ever practical and efficient, recognized the value of what the Illyrians had built and sought to expand and improve upon it.

The greatest contribution of the Romans was a leap forward in technology. They introduced new, more industrial methods for extracting oil that were far more efficient than the traditional ways of trampling olives with feet or squeezing them in sacks. Two key innovations spread throughout the Roman Empire, including to the newly incorporated province of Illyria. The first was the

trapetum, a revolutionary type of mill. It consisted of a large, circular stone basin, like a giant mortar, with two heavy, wheel-shaped millstones that were rolled around a central post. This machine could crush a large quantity of olives into a uniform paste quickly and effectively. The second invention was the

torcular, or beam press. After the olives were crushed in the trapetum, the paste was scooped into flexible, woven baskets. These baskets were stacked on a stone base, and a massive wooden beam was lowered onto them using a powerful winch or screw mechanism. The immense pressure squeezed every last drop of precious oil from the paste.

The physical proof of this technological upgrade can still be seen in Albania today. Archaeologists have unearthed the remains of these Roman-style mills and presses in the ruins of ancient cities like Bylis, Kostar, and Kamenicë. These stone artifacts are the silent gears of a once-thriving industry. The oil produced in this region under Roman rule was highly prized and became known as

Olea Liburnicum, a famous Illyrian product that was traded across the empire. To facilitate this trade, the Romans used standardized clay jars called

amphorae. These large vessels were the shipping containers of the ancient world, designed to be stacked efficiently in the hulls of ships, allowing Illyrian olive oil to travel safely across the Mediterranean to distant markets. The Romans’ vast network of paved roads and bustling ports further integrated the region’s olive oil into the powerful economy of the empire, bringing new levels of prosperity to the olive growers of Illyria.

Table 1: Ancient Olive Oil Technology in Illyria

To better understand the tools used by ancient producers, the following table provides a simple guide to the key technologies of the era.

| Tool Name | Period of Use | Material | Function (Simple Description) | Found In/At |

| Foot Pressing | Pre-Roman / Traditional | Wood, Sacks | People stomped on olives in a bag to squeeze out the oil. | Household use |

| Trapetum | Roman | Stone, Wood | A big stone mill with two wheels to crush olives into a paste. | Bylis, Kostar |

| Torcular | Roman | Wood, Stone | A giant lever or screw that pressed woven baskets of olive paste. | Roman-era sites |

| Pithoi / Amphorae | Greek / Roman | Clay | Large jars used to store and ship olive oil. | Apollonia, Durrës |

Part II: Surviving Empires

Chapter 4: A Flame Through the Dark Ages

After the Western Roman Empire crumbled in the 5th century AD, the lands of Albania became a province of the vast and powerful Eastern Roman Empire, better known as the Byzantine Empire. For nearly a thousand years, from its capital in Constantinople, Byzantium dominated the eastern Mediterranean. Throughout this long era, olive oil production remained a vital part of life in the Albanian territories. The Byzantine Empire as a whole was an enormous producer and exporter of olive oil, and its lands in the Balkans, including Albania, were an important part of this economic machine. However, the nature of production began to change. The massive, industrial-scale operations of the Roman era gave way to a more localized system. While trade certainly continued, production became more regional, with many families tending their own small groves to produce oil for their own consumption or for sale in nearby towns and markets.

This deep-rooted family tradition proved to be incredibly resilient, surviving through centuries of change and conflict. A particularly vivid example of the olive’s cultural importance comes from the 15th century, during the time of Albania’s national hero, Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, who led a legendary resistance against the encroaching Ottoman Empire. In this era, the olive tree was held in such high regard that a powerful tradition took hold: as a sign of blessing and a foundation for their future, a young couple was required to plant ten olive trees before they could be married. The value of these trees was so well understood that archives from Skanderbeg’s time even included detailed inventories of the olive trees owned by citizens, much like a modern government might track valuable property.

Following the eventual conquest by the Ottoman Empire, which would rule Albania for nearly 500 years, the agricultural landscape was largely defined by a feudal system where most people were subsistence farmers, growing just enough to feed their families. The Ottoman Empire maintained a vast internal trade network, and records show that olive oil from its Mediterranean territories was a key commodity, shipped to regions that could not grow olives, such as Crimea. Within Albania, however, production remained mostly a small-scale, traditional affair. Families continued to rely on the ancient methods passed down through generations. They used simple stone mills, often turned by a donkey or an ox, to crush their olives and produce the oil that was essential to their daily lives. While most of this oil was for local use, historical documents from the 17th and 18th centuries show that there was still some export trade, with olive oil from the areas around Tirana being shipped across the Adriatic to the bustling markets of the Republic of Venice.

This shift from the large-scale, centralized production of the Roman period to a smaller, family-based model during the Byzantine and Ottoman eras was not a step backward. It was a brilliant strategy for cultural and economic survival. In a world of constant political instability, where empires rose and fell, large, state-run facilities would have been vulnerable to disruption and collapse. By embedding the cultivation of the olive tree so deeply into the life of the family unit—making it a prerequisite for marriage, a source of daily sustenance, and a measure of household wealth—the tradition was decentralized and made incredibly strong. Even if a distant emperor or sultan fell, the Albanian family would continue to care for its trees, preserving the ancient knowledge, the precious genetic stock of the local olive varieties, and the profound cultural importance of its golden oil. The tradition became a grassroots movement, ensuring its flame would never be extinguished.

Chapter 5: The Dawn of Modernity

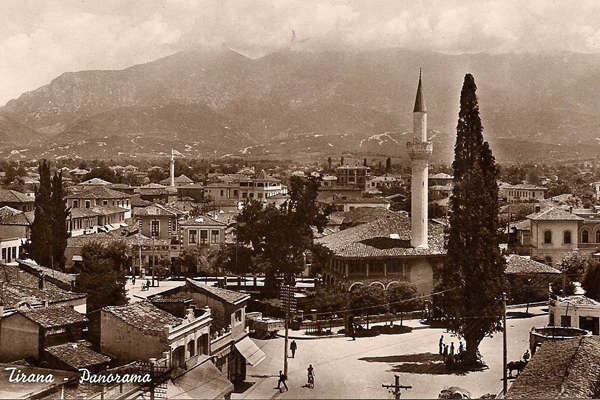

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, the olive groves of Albania presented a landscape that would have been familiar to a Roman farmer from two millennia earlier. The methods of cultivation and production had remained largely unchanged for centuries. The industry was defined by small-scale, family-based agriculture. Each autumn, families would harvest their olives and take them to a local mill, or fabrika vajit ullirit, for pressing. These mills were a common feature of the countryside. An inventory taken in 1940, well into the modern era, counted 546 such oil mills scattered across Albania. The vast majority, nearly 88%, were concentrated in the country’s historic olive-growing heartlands: the regions of Vlora, Delvina, Mallakastra, and Tirana.

However, amidst this sea of tradition, a powerful seed of modernity was planted. In 1897, in the city of Tirana, the first modern olive processing factory was established. This was a landmark event. It was one of the very first industrial factories of any kind to be built in Albania during the final decades of the Ottoman Empire. This factory represented a monumental shift in thinking. A traditional, animal-powered stone mill serves the needs of a single village or a handful of families. A factory, by its very nature, is built for commerce on a much larger scale. It requires a consistent and substantial supply of raw materials, far more than any single family could provide, and it is designed to produce a standardized product for a wider market.

The appearance of this factory was not just a technological development; it was a sign of a changing world. It coincided with a period when the old Ottoman Empire was attempting to modernize and, more importantly, when Albanian national consciousness was on the rise. The factory can be seen as a physical symbol of a new ambition: to transform olive oil from a product of household subsistence into a commercial commodity that could help build a national economy. It was the first glimmer of a vision for an Albanian olive oil industry.

This vision, however, would face immense challenges. When Albania finally declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1912, it was a nation with a profoundly underdeveloped economy. Centuries of feudalism and isolation had left it with almost no infrastructure. Good roads were virtually nonexistent, making trade between regions nearly impossible. Most families still lived a life of self-sufficiency, producing their own food, clothing, and tools. The ancient olive groves were a vital and cherished part of this landscape, but the journey to transform this traditional craft into a modern, competitive industry was only just beginning, and it would be a journey fraught with peril and upheaval.

Part III: A Century of Upheaval and Rebirth

Chapter 6: The Communist Experiment

The 20th century was a period of violent and radical change for Albania, and its ancient olive groves were caught in the storm. The decades following the country’s independence in 1912 were marked by instability, foreign occupation during two world wars, and profound economic hardship. This turmoil took a devastating toll on the olive sector. In what must have been a period of widespread neglect and destruction, the number of olive trees in the country plummeted dramatically. According to historical agricultural records, Albania was home to an estimated 8.1 million olive trees in 1912. By 1946, after the end of World War II, that number had fallen to just 1.768 million—a loss of more than three-quarters of the nation’s olive heritage.

After the war, the new communist government, led by the dictator Enver Hoxha, set out to completely remake the country according to a strict Stalinist model. This meant a total transformation of agriculture. The first step, in 1946, was a “land-to-the-tiller” reform, which broke up the old, large estates and redistributed the land among peasant families. This was a popular move, but it was short-lived. Soon after, the government began the brutal process of collectivization. Starting in the 1950s and completed by 1967, farmers were forced to give up their newly acquired private land and join massive, Soviet-style collective and state farms. The ancient tradition of family ownership, which had sustained the olive groves for millennia, was wiped out by state decree.

Under the new system, the olive was identified as a strategic crop, essential for the government’s goal of achieving national self-sufficiency. From 1955 until the regime’s collapse in 1990, the state poured resources into agriculture, establishing vast new olive plantations, particularly on the fertile coastal lands. The state farms, which functioned like industrial organizations, were given the best land, the best equipment, and the most investment. This state-driven expansion was quantitatively successful, significantly increasing the number of olive trees and the total area under cultivation. The regime became so confident in its olive expertise that in the 1970s, as part of a bilateral project with its then-ally China, Albania sent 1,500 seedlings of its prized native Kalinjot variety from Vlora to help establish olive cultivation in Asia.

This period created a profound paradox. On the one hand, the communist state planted millions of new olive trees, creating a huge physical asset for the nation. On the other hand, by destroying private ownership and forcing farmers into collectives, it severed the deep, personal, and generational connection between the people and their land. The stewardship of the olive tree was no longer a sacred family tradition passed down from parent to child; it was a centrally planned industrial task, dictated by officials in Tirana.

The state could command the planting of trees, but it could not replicate the centuries of accumulated wisdom, the intimate knowledge of the land, and the profound sense of cultural ownership that had made the olive groves so resilient. This created a hollow industry—impressive in its scale but lacking the deep cultural roots that had allowed it to survive for 3,000 years. This fragility would be exposed with shocking speed when the communist state itself began to crumble.

Chapter 7: The Lost Groves

The fall of communism in the early 1990s plunged Albania into a period of profound chaos and social breakdown. The rigid, top-down control that had defined the country for nearly half a century vanished overnight, and the vast state and collective farms, including the massive olive plantations, were left without owners or managers.

The result was a catastrophe for the nation’s olive heritage. In the turbulent transition period between 1991 and 1995, a wave of destruction swept through the countryside. Amidst the confusion and disputes over who owned what, an estimated 1.2 million olive trees were damaged, cut down for firewood, or simply abandoned to die. The total number of trees in the country, which had been artificially inflated during the communist era, collapsed once again, falling to a low of just 3.5 million by 1996.

Faced with this crisis, the new democratic government made a momentous decision. Instead of trying to return the land to the families who had owned it before communism—a complex and potentially divisive process known as restitution—it opted for a policy of distribution.

The land from the former state and collective farms was divided up and distributed equally among all rural households living there at the time. While this policy was born from a desire for fairness and a clean break from the past, it had a lasting and dramatic consequence: extreme land fragmentation. The enormous, unified state plantations were shattered into hundreds of thousands of tiny, disconnected parcels of land.

This fragmentation is the single most important legacy of the 20th century for Albania’s olive industry. Today, the average Albanian farm is incredibly small, measuring only about 1.2 hectares (around 3 acres), and is often split into four or five separate, non-contiguous plots. An estimated 80% of all farms in the country are less than 2 hectares in size.

This structure makes modern, efficient farming nearly impossible. It is difficult to use machinery, coordinate pest control, or achieve economies of scale when your property is a patchwork of tiny plots scattered across a hillside.

The high production costs and relatively low yields that challenge Albania’s olive oil producers today are a direct historical consequence of this violent swing from one extreme to another. The forced collectivization of the communist era erased centuries of family ownership, and the radical fragmentation that followed the collapse of that system created a new set of seemingly intractable problems.

It was only after a measure of political and social stability was restored around the year 1999 that the slow and difficult process of recovery could truly begin. Farmers once again started to invest in their land, and the number of olive trees began a steady climb, eventually surpassing 10 million in the decades that followed, setting the stage for a modern rebirth.

Part IV: The Olive Today and Tomorrow

Chapter 8: Albania’s Modern Harvest

The 21st century has marked a period of remarkable recovery and growth for the Albanian olive sector. After the devastation of the 1990s, a combination of government support, private investment, and the enduring resilience of its farmers has led to a significant rebound. The number of olive trees in the country has expanded dramatically, growing from around 8 million to approximately 12 million in the last decade alone. This has resulted in a surge in production, which has nearly tripled since the early 2000s. In the years before 2020, annual olive oil production hovered between 10,000 and 13,000 tons; in the past few years, the annual average has jumped to over 20,000 tons, with a record-breaking harvest of 26,000 tons in the 2021/22 season.

This modern harvest is concentrated in the country’s traditional olive-growing heartlands. The main regions for olive oil production are the coastal and central counties of Fier, Vlora, and Elbasan. Meanwhile, the historic region of Berat has become the primary center for the production of table olives. The overall olive cultivation zone forms a continuous belt that runs down the entire western side of the country, from Shkodra in the north to Saranda on the Ionian coast, and pushes inland along the fertile river valleys.

Despite this impressive growth, the industry is grappling with a set of deep-seated challenges, many of which are direct legacies of its turbulent history.

- Fragmentation: The small, scattered plots of land created in the 1990s remain the biggest obstacle to efficiency and profitability. It is difficult for farmers to modernize or mechanize, which keeps production costs high.

- Infrastructure: In many rural areas, the infrastructure has not kept pace with the growth in production. Poorly maintained roads make it a challenge to transport the freshly picked olives to the mill quickly—a critical step for producing high-quality oil. Some farmers report having to use donkeys and mules to carry their harvest, a method one farmer described as being “like the Middle Ages”.

- Labor Shortage: Albania has experienced a mass emigration of its young people in search of better opportunities abroad. This has left the agricultural sector with an aging workforce, creating a severe labor shortage. This is particularly problematic for olive farming, as the hilly terrain often requires that the olives be harvested by hand, a labor-intensive and costly process.

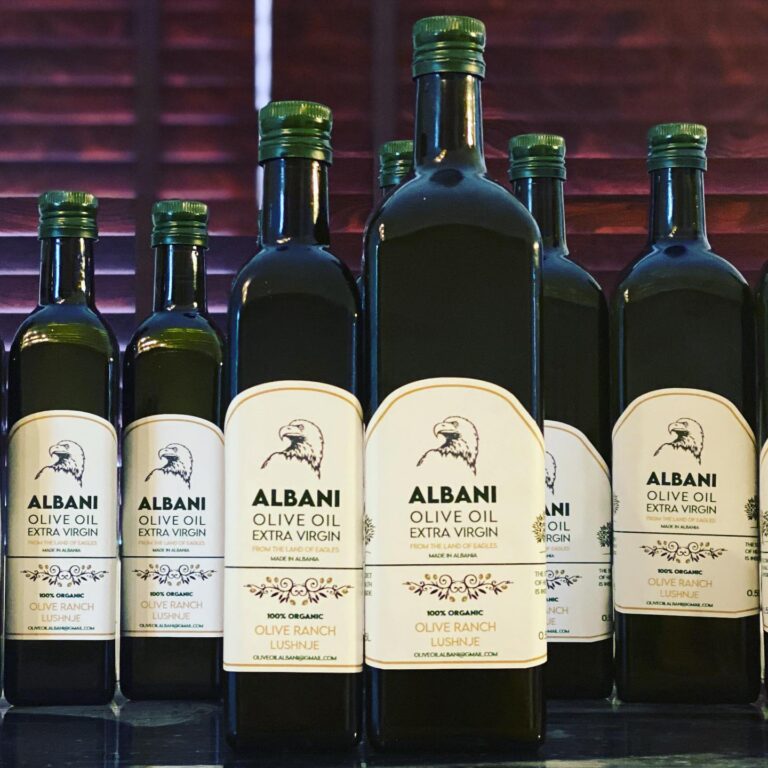

- Export and Branding: While production has soared, Albania has struggled to establish itself as a high-value exporter. The vast majority of its exported oil is sold in bulk at low prices to larger producers in Italy, Spain, and other countries, who then bottle it and sell it under their own brands. Creating a strong international identity for “Albanian Olive Oil” and ensuring consistent quality control remain major hurdles.

Yet, alongside these challenges, there are clear signs of progress and immense potential. The number of modern olive mills equipped with the latest Italian technology has increased significantly, which is dramatically improving the quality of the oil being produced. A new generation of ambitious, quality-focused producers is emerging. These small companies are bottling their own oil, focusing on native varieties, and winning prestigious awards at international competitions. They are proving, bottle by bottle, that Albanian olive oil can stand with the very best in the world.

Table 2: Albanian Olive Oil at a Glance (Recent Years)

The following table provides a summary of key statistics for Albania’s modern olive oil industry.

| Metric | Figure | Year(s) | Source(s) |

| Number of Olive Trees | ~12 million | ~2024 | |

| Main Oil Production Regions | Fier, Vlora, Elbasan | – | |

| Main Table Olive Region | Berat | – | |

| Avg. Annual Oil Production | ~20,670 tons | 2021-2024 | |

| Record Oil Production | 26,000 tons | 2021/22 | |

| Per Capita Consumption | 8.7 kg | 2022/23 | |

| Total Olive Production (2019) | 98,313 tons | 2019 | |

| Export Value (Jan-Aug 2023) | €25 million | 2023 |

Chapter 9: A Taste of the Land: Albania’s Native Olives

Perhaps Albania’s greatest treasure is not the quantity of its olives, but their unique identity. The country is home to a remarkable genetic heritage, with more than 28 native olive varieties that have adapted over millennia to the local soil and climate. This is a rich biodiversity that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. While many varieties exist, the country’s olive landscape is dominated by six primary native cultivars, each historically linked to a specific production zone.

- Kalinjot: This is the undisputed king of Albanian olives. Originating in the southern region of Vlora, it is so successful that it is the only native variety widely planted outside its home region, now accounting for nearly half of all olive trees in the country. Its oil is prized for its harmonious and balanced flavor, with a medium fruitiness and notes of green grass, apple, and almond, all complemented by a pleasant bitterness and a peppery finish.

- Kokërmadh Berati: Hailing from the historic region of Berat, this is a versatile, dual-purpose olive. Its round, medium-sized fruits are excellent both for making oil and for being cured and eaten as table olives.

- Ulliri i Bardhë i Tiranës (White Olive of Tirana): As its name suggests, this variety is native to the central region around Tirana and Durrës. It produces a more delicate and aromatic oil, with light, pleasant notes of apple, almond, spices, and fresh herbs. It is also known for having a high content of oleic acid, a healthy monounsaturated fat.

- Mixan: Grown in the highlands of Elbasan and Peqin, the Mixan olive contributes a distinctive and prized aroma and flavor, making it a key component in many regional blends.

- Krypsi Krujës: This variety is native to the area around the historic town of Krujë, the stronghold of Skanderbeg.

- Kallmet: From the northern regions of Lezhë and Shkodër, this olive shares its name with a famous native Albanian grape. The oil from the Kallmet olive is known for its bright green color, fresh fruity aroma, and a well-balanced taste with a hint of spiciness.

The unique and wonderful flavors of these oils are a direct reflection of their terroir—a French term that describes the powerful combination of a specific plant variety, the local soil and climate where it is grown, and the traditional human practices used to cultivate it. This is what gives Albanian olive oil its soul.

This soul is felt most strongly in the Albanian kitchen, where olive oil is not just an ingredient but the foundation of the national cuisine. As a Mediterranean country, Albania’s diet is rich in fresh vegetables, fruits, and fish, and olive oil is the fat that brings them all together. It is used generously in nearly every traditional dish, from slow-cooked stews and baked specialties like tavë kosi (baked lamb with yogurt) and fërgesë (a savory dish of peppers, tomatoes, and cheese), to the simple, fresh salads served with every meal.

In many parts of the country, a cherished morning tradition is to start the day with a piece of toasted bread drizzled with fresh olive oil and a sprinkle of salt or oregano—a simple, healthy, and delicious taste of the land itself.

While Albania may struggle to compete with its larger neighbors on the sheer volume of olive oil it produces, its future success may lie in telling the unique story of these native cultivars. The global market for food is increasingly interested in products with a unique origin, a compelling history, and a distinct flavor profile. By focusing on the quality and character of varieties like Kalinjot and Ulliri i Bardhë i Tiranës, Albania has the opportunity to move beyond being a supplier of a bulk commodity and become a celebrated producer of premium, high-value olive oils, each bottle a taste of the country’s ancient and unique heritage.

Chapter 10: The Olive Branch in Kosovo

While the histories of Albania and Kosovo are deeply intertwined, their agricultural stories, particularly concerning the olive tree, follow very different paths. The user’s query included Kosovo, and it is important to address its story with clarity. Based on the available historical and archaeological evidence, Kosovo does not share the same ancient, continuous tradition of large-scale olive cultivation that defines coastal and central Albania. The primary reason for this is geography. The olive tree is a quintessential Mediterranean plant; it thrives in a climate with mild, wet winters and long, hot, dry summers. The coastal regions of Albania provide these perfect conditions. Kosovo, however, is located further inland in the heart of the Balkan Peninsula and has a more continental climate, which is generally less suitable for olive cultivation. In fact, archaeological and cultural evidence suggests that the symbolic fruit tree of ancient Dardania, the region that corresponds to modern-day Kosovo, was not the olive but the pear, known in Albanian as dardha, from which the region’s name is derived.

The modern agricultural story of Kosovo has been shaped by more recent and tragic events. The war in the late 1990s caused significant damage to the country’s entire agricultural sector, and its recovery has been a long and difficult process. In the post-war era, Kosovo’s farmers have faced a host of challenges, many of which are strikingly similar to those in Albania: a legacy of underinvestment, severe land fragmentation into small, inefficient plots, a lack of modern technology, and inadequate irrigation systems.

The focus of post-war agricultural development, often supported by international aid and government programs, has been on revitalizing the sectors where Kosovo has a natural comparative advantage, such as horticulture (the growing of other fruits and vegetables) and livestock farming. While there are some modern initiatives to cultivate olive trees in specific areas of Kosovo with suitable microclimates, these are recent developments and represent a new chapter rather than the continuation of an ancient tradition.

Despite the lack of a historical production base, olive oil is certainly a part of modern Kosovar life and cuisine. Through shared cultural and family ties with Albania, as well as the broader influence of Mediterranean and Balkan food culture, olive oil is a familiar product in Kosovar households. It is primarily an imported good, often coming from Albania itself, and is used in salads, cooking, and traditional dishes. However, it does not hold the same foundational, almost sacred, role in the cultural identity and historical memory of Kosovo as it does in the coastal regions of Albania, where the land and the people have been shaped by the olive tree for thousands of years. The absence of this deep history is not a lesser story, but a different one, and it highlights the profound way in which the natural environment—the climate, the soil, the very landscape itself—shapes the path of human culture.

An Enduring Legacy

The journey of the olive tree through Albanian history is an epic tale of endurance. It begins with a wild plant thriving on the Balkan Peninsula tens of thousands of years ago, a silent native of the land. It becomes a treasured crop in the hands of the ancient Illyrians, who recognized its power to provide not just sustenance, but wealth, status, and cultural identity. Under the Romans, its golden oil was transformed into a prized commodity, produced with new efficiency and shipped across a vast empire. Through the long centuries of Byzantine and Ottoman rule, the olive tree retreated into the heart of the Albanian family, becoming a symbol of continuity and a household staple that ensured survival in uncertain times.

The 20th century subjected this ancient tradition to its most violent tests. It was first embraced as a tool of communist ideology, its groves expanded on an industrial scale to serve the state’s ambition of self-sufficiency. Then, with the collapse of that regime, it became a victim of chaos, its trees destroyed and its vast plantations shattered into a thousand tiny pieces. Yet, the olive tree endured. The fact that the 3,000-year-old trees of Brret and Petrela still stand, and still bear fruit, is a powerful metaphor for the resilience of the Albanian people and their culture.1 They have weathered the storms of history, and their roots remain deep in the soil.

Today, the Albanian olive oil industry stands at a crossroads, shaped by both the burdens and the gifts of its past. The challenges of land fragmentation, aging infrastructure, and a shrinking rural workforce are the direct echoes of 20th-century upheaval. But the gifts are just as profound: a perfect Mediterranean climate, a renewed passion for cultivation, and, most importantly, a unique genetic heritage of native olive varieties found nowhere else on earth. The future of Albanian olive oil may not lie in competing with the industrial giants of the Mediterranean on quantity, but in telling its own unique story—a story of quality, of ancient traditions, and of the distinct, wonderful flavors of cultivars like Kalinjot and Ulliri i Bardhë i Tiranës. The golden thread, first spun in the Neolithic age, continues to be woven, connecting Albania’s deep past to a bright and promising future.

Works cited

- Olive and Olive Oil in Albania, From Antiquity Until the Middle Ages – Neliti, accessed September 15, 2025, https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/570381-olive-and-olive-oil-in-albania-from-anti-153ec675.pdf

- The origin and the old olives in Albania, – WordPress.com, accessed September 15, 2025, https://oliveresearchstation.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-origin-and-the-old-olives-in-albania.pdf

- Hairi Ismaili; Belul Gixhari. The origin of the olive in Albania – WordPress.com, accessed September 15, 2025, https://oliveresearchstation.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-origin-of-the-olive-in-albania.pdf

- Olive in the story and art in Albania – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299533090_Olive_in_the_story_and_art_in_Albania

- Olive tree as a way of life in the Albanian Riviera – Polis Press, accessed September 15, 2025, https://press.universitetipolis.edu.al/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/18.-Erida-Curraj.pdf

- Olive – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olive

- OLD OLIVES OF ALBANIA Hairi ISMAILI, Belul GIXHARI Albania …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://qrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/The-Old-olives-of-Albania_H.-Ismaili-B.-Gixhari.pdf

- Olive and Olive Oil in Albania, From Antiquity Until the Middle Ages, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.anglisticum.org.mk/index.php/IJLLIS/article/view/1074

- Olive in the story and art in Albania, accessed September 15, 2025, https://oliveresearchstation.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/2015_albania_olive-in-the-story-and-art-vlore_17_janar_2015.pdf

- Old olive trees evaluated between 1000 – 3000 years old. – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Old-olive-trees-evaluated-between-1000-3000-years-old_fig3_299533090

- Remains of olive presses in ancient Thouria of Messenia – Archaeology Wiki, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2016/07/06/remains-olive-presses-ancient-thouria-messenia/

- The Ancient Origins of Croatian Olive Oil | SELO, accessed September 15, 2025, https://seloolive.com/blogs/olive-oil/the-ancient-origins-of-croatian-olive-oil

- Albanian cuisine – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albanian_cuisine

- OLIVE OIL TRAILS AND HISTORY IN ALBANIA Historical Background Day 1: Shkodra & Kruja, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.beinalbania.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/5-Day-Olive-Oil-Trails-Albania-Itinerary.pdf

- History of the Olive Tree and Olive Oil – CRITIDA, accessed September 15, 2025, https://critida.com/history-of-the-olive-tree-and-olive-oil/

- Byzantine economy – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_economy

- Albania – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albania

- Albania – The Precommunist Albanian Economy – Country Studies, accessed September 15, 2025, https://countrystudies.us/albania/65.htm

- History of Albania. Timelines, ancient and modern Albania history. – CountryReports.org, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.countryreports.org/country/Albania/expandedhistory.htm?countryid=2&hd=r134a.aspx&al0065)

- Ottoman Commercial History | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-482?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190277727.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190277727-e-482&p=emailAYqeZyzt7PoDE

- Albanian Traditional Olive Oil – Aljeta, accessed September 15, 2025, https://aljeta.com/en_us/het-traditionele-albanie/

- Olive Oil Tour in Tirana – Albania, accessed September 15, 2025, https://albania.al/olive-oil-tour-in-tirana/

- Berat: The center of Albanian olive oil. – Aljeta, accessed September 15, 2025, https://aljeta.com/en_us/herkomst-berat-albanie/

- In 1897 the first Olive Processing Factory was established in Tirana …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/albania/comments/ayusmr/in_1897_the_first_olive_processing_factory_was/

- Olive in the story and art in Albania – WordPress.com, accessed September 15, 2025, https://oliveresearchstation.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/2015_albania_olive-in-the-story-and-art_aut-tirane_24_janar_2015.pdf

- ECONOMIC TRANSITION IN ALBANIA: POLITICAL CONSTRAINTS AND MENTALITY BARRIERS by MARTA MUÇO (ALBANIA) – NATO, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.nato.int/acad/fellow/95-97/muco.pdf

- People’s Socialist Republic of Albania – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People%27s_Socialist_Republic_of_Albania

- Land reform in Albania – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_reform_in_Albania

- II The Pre-Reform Economic System in: Albania – IMF eLibrary, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781557752666/ch002.xml

- Albania Study_4 – Marines.mil, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/Albania%20Study_4.pdf

- Albania – Economy, Agriculture, Tourism | Britannica, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Albania/Economy

- Albania’s olive groves – Paka Olive Oil, accessed September 15, 2025, https://pakaoliveoil.com/2023/12/22/albanias-olive-groves/

- Lessons from a diagnostic analysis of Albania’s Divjaka region – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.fao.org/4/w8101t/w8101t11.htm

- Albania – The Garden of Peace, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.thegardenofpeace.org/thegarden/albania-statistics/

- Olive Cultivation, Experts: High cost of production limits oil exports – Hashtag.al, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.hashtag.al/en/index.php/2023/01/11/kultivimi-i-ullirit-ekspertet-kostoja-e-larte-e-prodhimit-kufizon-eksportet-e-vajit/

- Albania intends to increase olive oil production – UkrAgroConsult, accessed September 15, 2025, https://ukragroconsult.com/en/news/albania-intends-to-increase-olive-oil-production/

- Albanian Olive Oil Exports Quadruple in First Quarter of 2023 …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/business/albanian-olive-oil-exports-quadruple-in-first-quarter-of-2023-officials-say/121667

- Albanians, Top Global Consumers of Table Olives • IIA – Invest in Albania, accessed September 15, 2025, https://invest-in-albania.org/albanians-top-global-consumers-of-table-olives/

- Map of Albania showing olive cultivation area (USAID, 2011) According… – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-Albania-showing-olive-cultivation-area-USAID-2011-According-to-Figure-2-the_fig1_221923433

- SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE OLIVE SECTOR IN ALBANIA – ASDO, accessed September 15, 2025, https://bujqesia.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/3-STUDIMI-I-ULLIRIT-ANGLISHT.pdf

- Albanian Producer Pairs Local Culture, Award-Winning Quality – Olive Oil Times, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/production/donika-olive-oil-founder-aims-to-elevate-albanian-olive-oil-globally/137855

- Emigration, Infrastructure Hamper Albanian Agriculture – Olive Oil Times, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/production/emigration-infrastructure-hamper-albanian-agriculture/136700

- Productive year in Vlora, but there is a lack of manpower in the villages – Euronews Albania, accessed September 15, 2025, https://euronews.al/en/productive-year-in-vlora-but-there-is-a-lack-of-manpower-in-the-villages/

- Factors Affecting the Olive Production Chain in Albania – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368951061_Factors_Affecting_the_Olive_Production_Chain_in_Albania

- Olive Sector Statistics – March 2025 – International Olive Council, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-sector-statistics-march-2025/

- Olive oil sales reach 25 million euros, an annual increase of 665 …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.panorama.com.al/en/shitjet-e-vajit-te-ullirit-arrijne-ne-25-mln-euro-rritje-vjetore-me-665-pas-prodhimit-rekord-si-ndikoi-thatesira-ne-vendet-e-evropes/

- Albanian Olives Varieties – Paka Olive Oil, accessed September 15, 2025, https://pakaoliveoil.com/2023/11/26/albanian-olives-varieties/

- Discover the Albanian Olives Behind Little Olive Oil, accessed September 15, 2025, https://littleoliveoil.co.uk/blogs/little-olive-oil-notes/discover-the-albanian-olives-behind-little-olive-oil

- Kalinjot Olives in Donika Olive Oil: The Heritage of Flavor, accessed September 15, 2025, https://donikaoliveoil.com/kalinjot-olives-in-donika-olive-oil-the-heritage-of-flavor/

- ORGANOLEPTIC CHARACTERIZATION OF MONO CULTIVAR EXTRA-VIRGIN OLIVE OILS IN ALBANIA – Journal of Hygienic Engineering and Design, accessed September 15, 2025, https://keypublishing.org/jhed/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/01.-Fatmira-Allmuca.pdf

- Elbasan Kokërmadh Olive – Arca del Gusto – Slow Food Foundation, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/ark-of-taste-slow-food/kokerrmadh-extra-virgin-olive-oil-from-elbasan/

- virgin olive oil production from the major olive varieties in albania – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270903617_VIRGIN_OLIVE_OIL_PRODUCTION_FROM_THE_MAJOR_OLIVE_VARIETIES_IN_ALBANIA

- Silver Label: Signature Extra Virgin Olive Oil – 750 mL – Black Horse Initiative, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.blackhorseinitiative.com/shop/p/silver-label-signature-extra-virgin-olive-oil-750-ml

- Mlita Olive Oil Production Albania, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.mlita.al/

- Kallmet Extra Virgin Olive Oil – Premium Quality | Me Zemër – Me …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://mezemer.com/en/products/extra-virgin-olive-oil-kallmeti-organic-albanian-biologic

- Culture of Albania – Wikipedia, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_Albania

- Si të Përdorni Vajin e Ullirit në Receta të Përditshme Shqiptare – Shkrela Olive Oil, accessed September 15, 2025, https://shkrelaoliveoil.com/si-te-perdorni-vajin-e-ullirit-ne-receta-te-perditshme-shqiptare/

- Archaeological Evidence about the Great Seal of the United States – ResearchGate, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382530300_Archaeological_Evidence_about_the_Great_Seal_of_the_United_States

- Crop Guide: Growing Olives – Haifa Group, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.haifa-group.com/olives-fertilizer/crop-guide-growing-olives

- (PDF) CHALLENGES OF AGRICULTURE SECTOR: CASE STUDY OF KOSOVO, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344286984_CHALLENGES_OF_AGRICULTURE_SECTOR_CASE_STUDY_OF_KOSOVO

- (PDF) Impact of Agricultural Policy in Development of Agriculture …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318535119_Impact_of_Agricultural_Policy_in_Development_of_Agriculture_Sector_Within_the_Period_of_1999-2015_in_Kosovo

- Restoring Kosovo’s Agriculture Sector After Conflict–IFDC’s …, accessed September 15, 2025, https://hub.ifdc.org/items/e00d73ee-7df2-4184-afac-31c0587cfc49

- Smallholders Are Not the Same: Under the Hood of Kosovo Agriculture – MDPI, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/12/1/146

- Growing Olive Oil Production in the Balkans, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/business/europe/growing-olive-oil-production-in-the-balkans/50771

How Olive Oil Shapes Middle Eastern Cuisine – Taqwas Bakery and Restaurant, accessed September 15, 2025, https://taqwasbakery.com/blogs/how-olive-oil-shapes-middle-eastern-cuisine